Sweat dripped from the temple of Arthur Lee as he completed another sprint under an Indian summer sun that turned the old Stanford Stadium into a frying pan.

It was late September, 1995, and the freshman, just days after arriving at Stanford from his home in South Central Los Angeles, was overwhelmed.

Short of breath and depleted of energy from heat and the sprints down the faded rose-colored track, Lee’s confidence dimmed, and this was only a conditioning workout for the basketball team.

Lee realized he was in over his head. Basketball was going to be tough. His classes were going to be even tougher. In every respect, he was going to have to perform at an entirely different level. He didn’t know if he could.

Hands on his hips, Lee leaned his head back and squinted at the coast live oaks peaking above the rim of the stadium, and wondered: How in heaven’s name and I going to make it at this place?

•••

•••

TWENTY YEARS AFTER his late-game heroics and game-changing steal keyed one of the most dramatic and important victories in Stanford basketball history, Lee often draws on that moment. A teacher in inner-city Chicago, Lee looks into the eyes of teenagers every day and senses the same fears. This time, he has the perspective to answer.

“I always think back to that time, when things seemed like they would be rough,” said Lee, an athletic director, P.E. teacher, and academic advisor at Chicago Bulls College Prep on the city’s Near West Side. “I didn’t know what was going to happen next. But I know this: I made it then, I can make it now.”

One of Lee’s favorite quotes comes from Martin Luther King, Jr.: “Take the first step in faith. You don't have to see the whole staircase, just take the first step.”

“That’s essentially how I live my life, that’s essentially how I try to teach my students. We don’t know. We don’t have all the answers. But just take one step at a time. You will succeed if you keep moving forward. Stanford was a good place to learn that lesson.”

Such are the legacies from the 1997-98 season, when Lee guided Stanford to the Final Four. It was a glorious season in a glorious era that Stanford, now under second-year Anne and Tony Joseph Director of Men’s Basketball Jerod Haase, seeks to recreate.

To do so, Haase has reconnected and renewed relationships to what he considers to be a Stanford basketball family. The Final Four team will be honored at Stanford’s regular-season home finale Saturday (4 p.m.) against Washington State.

An overtime loss to Kentucky ended the NCAA run in the semifinals, but player after player spoke to the shared experiences, conversations, and camaraderie that continue to inspire them today in their careers in basketball, business, finance, medicine, and even as a stay-at-home dad.

Now, as then, they share a respect among each other that remains rare for even the most successful teams. And it was enhanced by a certain madness.

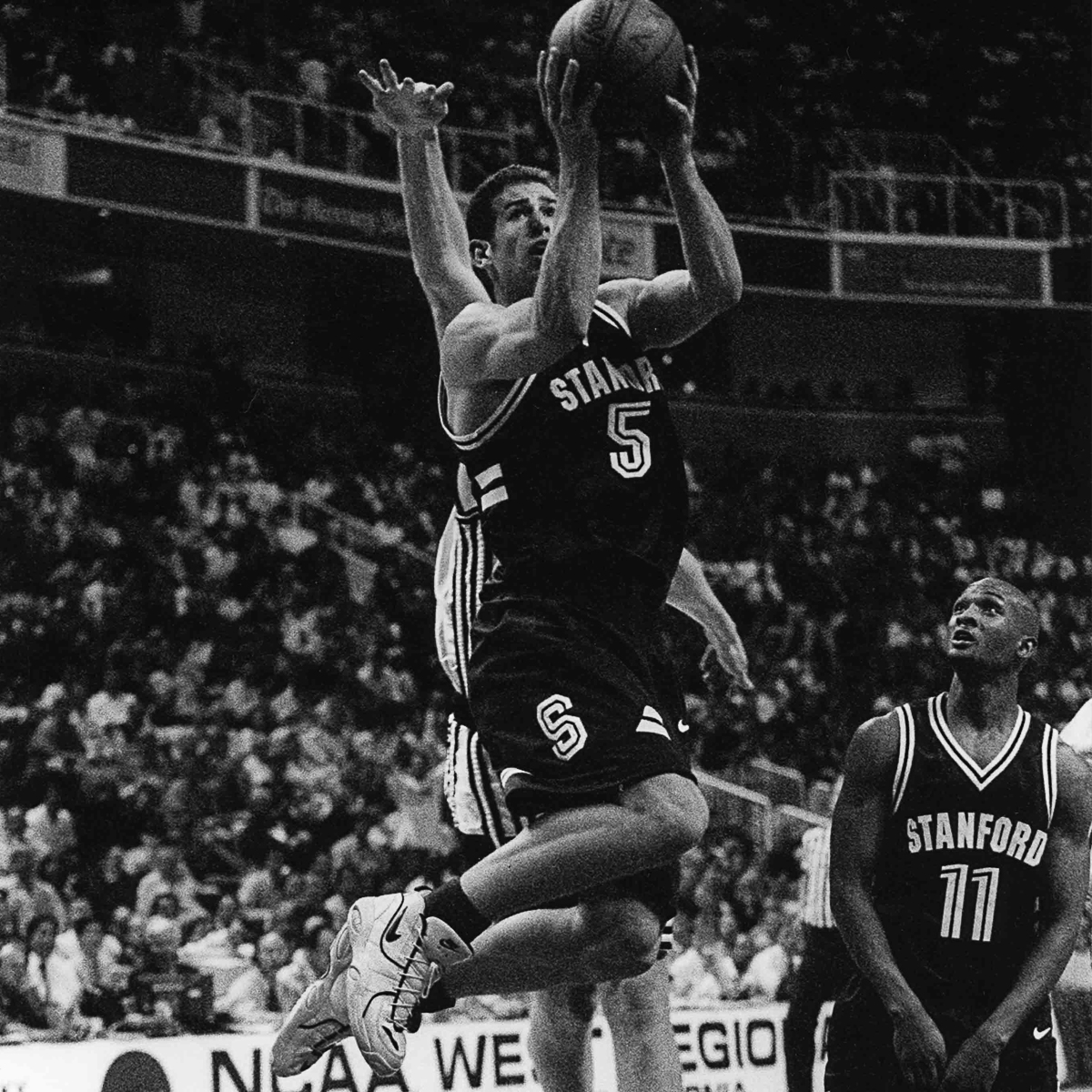

With Stanford trailing Rhode Island in the Midwest regional final with two minutes to go, Lee scored 13 of Stanford’s final 19 points. Stanford still trailed by six with 59 seconds to go, but Lee scored on a three-point play and knocked the ball out of an opponent’s hands to teammate Mark Madsen with 26 seconds left. He wheeled to the basket and …

"MADSEN STUFFED IT, MADSEN STUFFED IT . . . AND . . . HE . . . WAS . . . FOULED!" bellowed Bob Murphy on a memorable radio call.

Stanford’s 79-77 victory returned the Cardinal to its first Final Four in 56 years. And, at an institution teeming with NCAA championships and Rose Bowl triumphs, there is no greater moment of jubilation in 127 years of Stanford sports than Madsen’s feral fit of enthusiasm in reaction to his dunk.

•••

•••

ALL SEASON, STANFORD captain Peter Sauer, whose father was president of the St. Louis Blues hockey team, said that if Stanford made the Final Four, and went through the Midwest regional in St. Louis to do so, a hot tub run would be in the offing.

Sure enough, afterward, there was Sauer with a handful of cigars, and a mission.

“We got these stogies, man,” Sauer said. “Going to hit the hot tub. Oh yeah, oh yeah. We’re hitting the hot tub.”

With Lee and teammate Kris Weems in tow, Sauer weaved through the Kiel Center catacombs to the Blues’ training room, where a soothing, steaming cauldron awaited. Coughing and hacking, the trio savored the delights of victory.

“Pete Sauer was such a good guy and teammate, he just wanted us to celebrate in a special way,” Weems said.

At 6-7, Sauer was among eight players at that height or above, making them the tallest team in school history. Sauer, a small forward, was a strong athlete who could shoot and was willing to pick up any role the coaches needed, inside or outside.

As a freshman, he made an impression for reading the Wall Street Journal in the back of the bus. He made friends easily and served as “a connector,” between social groups, said Casey Jacobsen, who was hosted by Sauer on a recruiting trip.

Sauer was universally loved and respected by teammates. He clearly was his own man, and had a magnetism that inspired others to follow. He was confident without being cocky, and could push and encourage at the same time.

“You know you have those friends that you want to be around?” said guard Mike McDonald. “They seem like they just understand everything and they just get it? That was Pete. He was selfless, tough, and dedicated. Those are some of the things that ’98 team really embodied.”

“He was the best guy ever,” said close friend and roommate Steve Coughlin, better known as “Stanford Steve,” to ESPN viewers. “The best man. The best teammate. The best friend. The best guy. The best dad.”

In 2012, Sauer collapsed and died at a pickup game in White Plains, New York. The official cause is simply, “sudden death,” which implies cardiac arrest, but without the symptoms. The exact cause remains a mystery.

When Haase reached out to members of the Final Four team, there was a recurring theme of their conversations, that Sauer should be honored in some way, for what he meant to the team and the person he was. In response, Haase created The “Peter Sauer Captainship.”

“I’ve wanted to make our captainship more real, more valuable, and a more important part of the program,” Haase said. “My plan is to continue this as long as I’m the coach here.”

Haase received the blessing of Peter’s widow, Amanda, who will be Stanford’s honorary captain on Saturday.

Amanda had difficulty coping after Peter’s death, but made a decision to pull herself together, stop moping, and seize the day as a way to set an example for their three daughters. Amanda chose to dedicate herself to football officiating.

Amanda was a three-sport athlete in high school and a football fan. She and Peter were attending a high school football game in 2011 in Westchester County, New York, when a youth-league official heard her complain about a non-call and encouraged her to come to one of their meetings.

More than six years later, Amanda is among college football’s most promising officials. Working for the Mid-America Conference, she is the only female head referee in the Football Bowl Subdivision and, last year, became the first female head referee to call a power-five conference game, in a Big Ten clash at Rutgers. Her goal is the NFL.

“It was so important for my girls to see that in me,” she said. “Not only after he died, but in life now. There’s not a female referee? So what. Let’s go. I’m ready for whatever life brings. There’s absolutely nothing we can’t get through.”

•••

•••

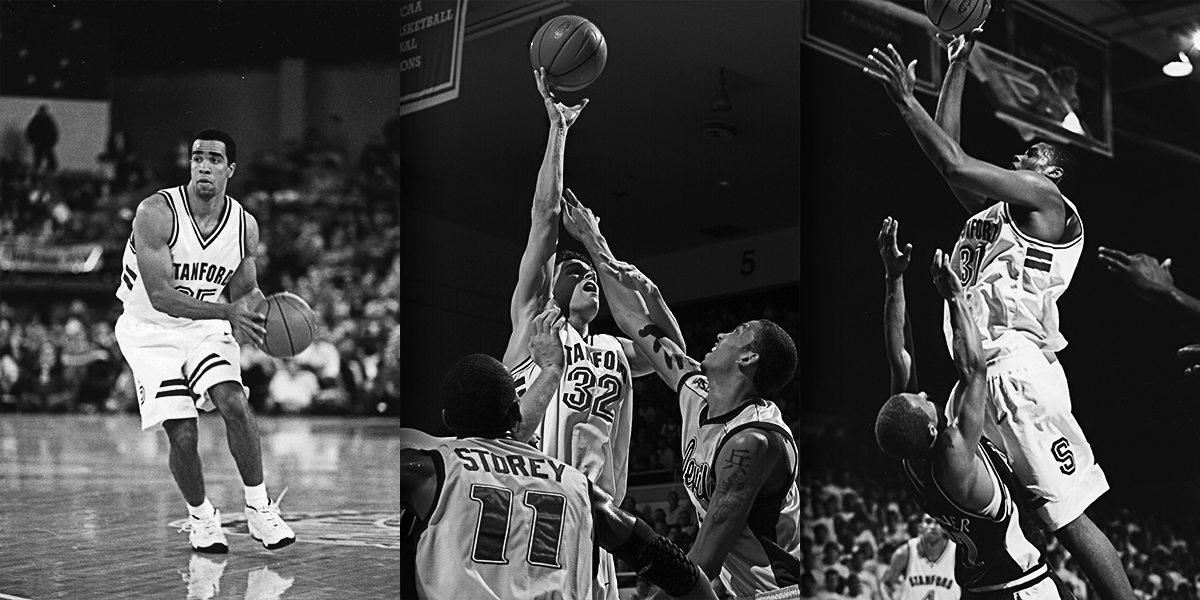

THE TEAM WAS coming off a Sweet Sixteen berth and a third consecutive NCAA tournament appearance. It had an imposing lineup anchored by 7-1 center Tim Young and intense sophomore power forward Madsen. Twins Jarron and Jason Collins were highly-touted freshmen, and Mark Seaton and Pete Van Elswyk were veteran forwards who could have started for nearly anyone else in the Pac-10.

Collapse into a zone defense? No chance! Sharpshooters Weems, Ryan Mendez, Sauer, and David Moseley made you pay.

“I remember Coach Montgomery said he wasn’t sure if he had no stars on his team or 15,” Seaton said. “We were really the consummate team. One unit on the court.”

Until the Collins twins arrived, there was nary a McDonald’s All-American in sight. But their success inspired top recruits like future All-Americans Jacobsen and Josh Childress. The Cardinal won Pac-10 championships the next four seasons, touched a No. 1 ranking, and maintained a run of 13 NCAA tournament appearances in 14 years.

“I wouldn’t have come to Stanford if it wasn’t for that team,” Jacobsen said. “I loved Stanford and what it offered, but I had my doubts on whether they could compete at the highest level. For Stanford to prove it, that was like the cherry on the top of the sundae for me.”

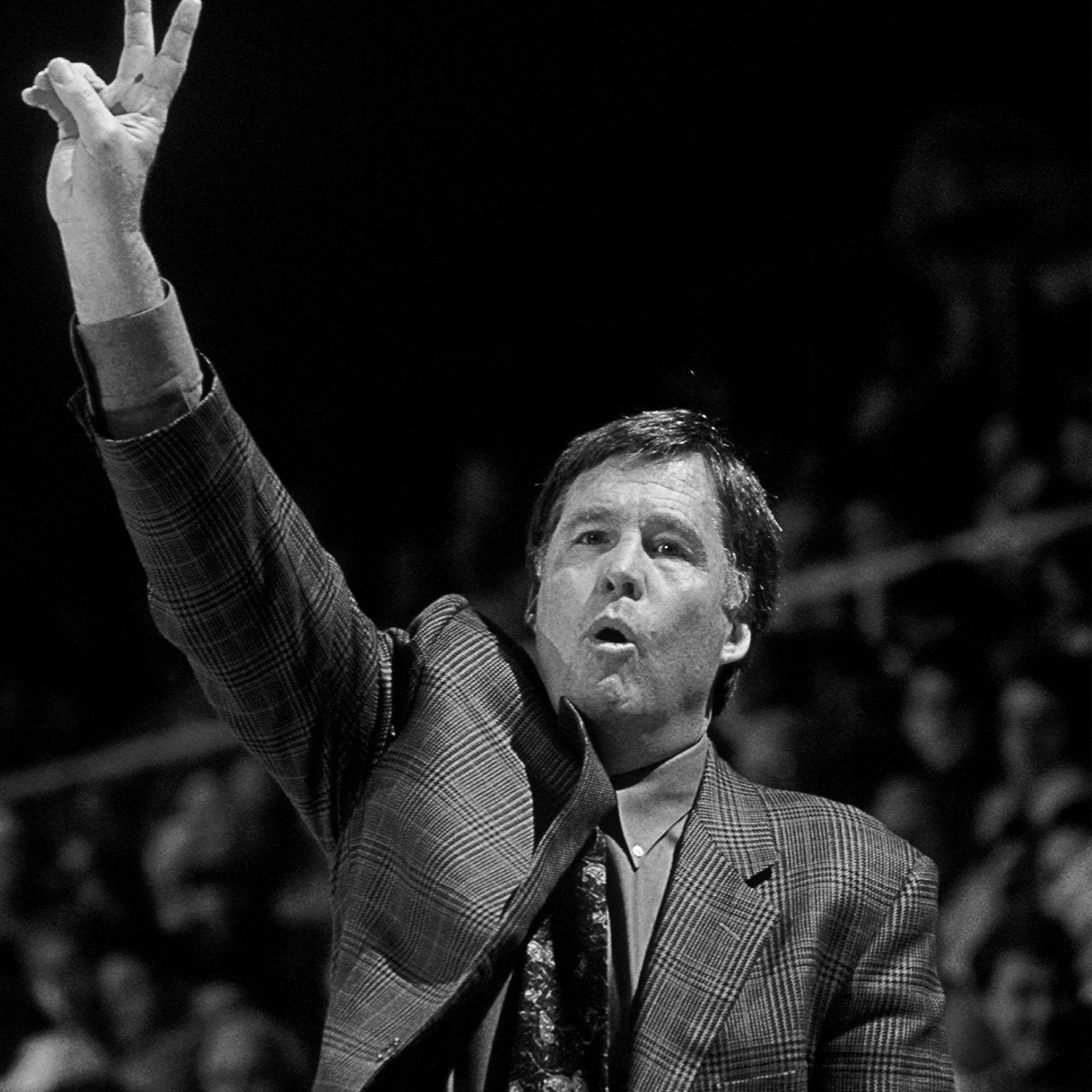

Coach Mike Montgomery had a gift for strategy and preparation. He compiled about 70 plays and expertly defined roles, convincing his players to believe in them.

“We were coached to be unselfish and to always play for each other,” Weems said. “Those were hallmarks of Montgomery’s philosophy and also a large part of everyone’s character.”

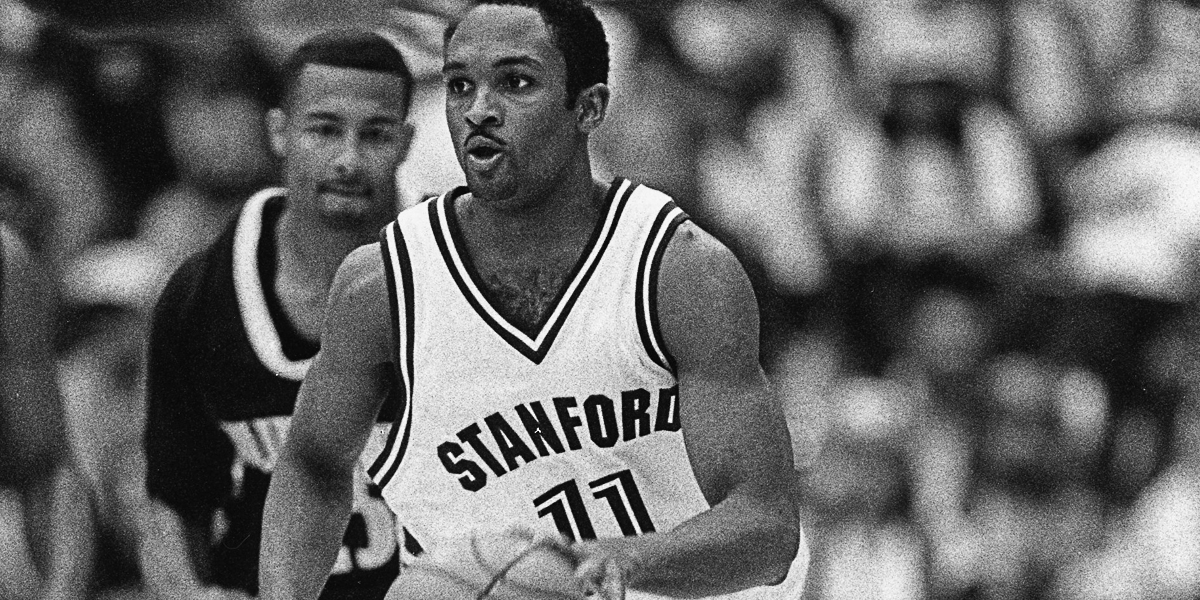

Many figured the Cardinal had reached its high-water mark when Brevin Knight, the greatest point guard in school history, graduated in 1997. His successor was the unproven Lee.

“People slighted my ability,” Lee said. “That was the biggest mountain I had to climb psychologically, because every minute I stepped on the court, I felt I had to prove something, that I was as good as Brevin was.”

During Lee’s freshman year, during a Saturday morning scrimmage at Burnham Pavilion, “I don’t know what Art did – swore or gave a little glare – but it ticked Brevin off,” said Rafael Ruano, the head student manager. “The dude literally stole the ball four or five consecutive possessions before Art crossed halfcourt. It got to the point where Coach Montgomery had to say, ‘that’s enough."

The jawing continued on the walk back to the locker room.

“They absolutely pushed each other,” Ruano said. “It made Art a much more complete player. After being defended by Brevin for a year, everything was easy.”

Madsen was a 6-8 force inside and so fiery that he earned the nickname, “Mad Dog.” But off the court, he was nice and wholesome as could be.

When a reporter quoted Madsen as yelling, “Damn!” in reaction to a big play, Madsen called him out: “I know I didn’t say that, because that’s a word I would never say.”

At one practice, when Stanford was down a big man, walk-on guard David Bennion was ordered to guard Madsen.

“I was banging him with all my might, but I could barely move him an inch,” Bennion said. “He kept telling me what a nice job I was doing. It felt like that conversation in ‘The Princess Bride’ between Andre the Giant and the Man in Black.”

Jarron Collins, the 6-9 freshman, saw the other side of Madsen.

“My first day of practice, Mark Madsen held a deep post seal against me,” Collins said. “I couldn’t get around him. I quickly realized I needed a lot more time in the weight room and better technique to defend Mad Dog.”

With a roster of talented and competitive players, competition for spots was fierce.

“Only five guys start, but eight or nine guys think they can start,” Moseley said. “There were fistfights. I got in a fight on my recruiting visit. Hey, you got in a fight one day, shook hands after practice and ate dinner together and that was it. If it was a real bad one, maybe you didn’t talk for two days.”

Mendez scored an astounding 38.2 points and grabbed 18.3 rebounds as a senior at Burleson (Texas) High, but at Stanford, it was difficult to wedge his way into the rotation. When he felt he wasn’t receiving meaningful minutes, his stomach got so tied up that he became physically ill after games. The only option for Mendez was extra work, and he regularly broke into Maples Pavilion late at night.

“I didn’t have a key,” he said. “But one of the doors you could manipulate ever so slightly and end up getting in. You had to put your right foot on the edge of one of the double doors, push the bottom in and then reach your hand inside there and press the lever down. I’m just glad they didn’t fix that door.”

Kamba Tshionyi started only once in his career – the price of being stuck behind Knight and Lee. While he never was content with his lack of playing time, he accepted his role as a behind-the-scenes leader who often knew more about the opponents than the opponents themselves, and could counsel teammates by pulling them aside and letting them know what to look for.

Seaton had a preference for cliched inspirational sports rock, so the locker room was a bastion for the Rocky theme song and Survivor’s “Eye of the Tiger.” Such was the background music to Stanford’s 18-0 start. The Cardinal went 15-3 in the Pac-10 and would finish 30-5 overall. Weems scored 34 points against Oregon and beat Washington with a length-of-the-floor run and three-point buzzer beater. Ten players averaged at least 10 minutes a game.

Three times during the season, the Cardinal swept conference road trips. On the return to campus, when the bus crossed El Camino Real from Embarcadero, the team broke into a special song. Some of the lyrics remained the same and new ones were adapted based on the vanquished teams. Sauer was in charge of the lyrics and would lead. It was a team tradition that guard Michael McDonald took over the next year and passed along when he graduated.

“That was always a special moment, just the camaraderie we had,” McDonald said. “We’d get the song ready, get our vocal cords ready, and when he hit the sign with the football schedule on it, we would sing.”

What, exactly, did they sing? McDonald refused to say.

•••

•••

THERE WAS SOME luck involved in Stanford’s NCAA run. Stanford avoided upset victims Clemson and Kansas (with Paul Pierce and Raef Lafrentz). Mendez changed the first-round game against Charleston by hitting consecutive three’s and Moseley hit a big three to beat the shot clock and help shut down Purdue, 67-59 in the Sweet Sixteen.

The night before the Rhode Island game, Lee and roommate Seaton stayed up until 2 a.m. debating the possibilities of reaching the Final Four. Despite coming from different backgrounds -- Lee from inner-city L.A. and Seaton from suburban Orange County -- they had a strong bond that was fortified by their parents.

Before every home game, Seaton’s father, Bruce, left in the morning to pick up Arthur’s father, Arthur Sr., and drove up to Stanford. Afterward, they turned around and drove back so that they could be at work by 8 a.m. Two days later, they would do it again. In four years, they never missed a home game.

That night in St. Louis, Seaton agonized over Stanford’s chances.

“Don’t worry Seaton,” Lee said. “We gonna make it. We’ll definitely make it.”

Facing a big late deficit, Montgomery extended the game by ordering fouls and calling timeouts, just hoping Rhode Island would make a mistake. And it did, missing a free throw at the front of a one-and-one that opened the door for the Cardinal.

Montgomery refused to call it his best coaching job ever.

“No,” he said. “It was the best stretch of playing that the players ever did. You do what you have to do relative to the situation. Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t.”

•••

•••

AT THE FINAL FOUR in San Antonio, the Stanford Tree was chased away by authorities, who probably expected a more traditional mascot. That was before The Tree was asked by a reporter, “If you were a person, what kind of person would you be?”

As Stanford prepared to take the Alamodome court, the Stanford players were met in the hallway by actress Ashley Judd, a huge Kentucky fan.

“I remember she had an evil disposition as if she was possessed,” Mendez said. “She looked directly at our team with those evil eyes and said, ‘You guys are gonna lose.’ I smirked and remembered thinking that comment was about as classless as one can get. To this day, I refuse to watch her movies.”

The game was a battle royale. Stanford led, fell behind, and dueled back-and-forth the rest of the way. Lee, as focused as ever, hit all five of his 3-point attempts and was perfect from the free-throw line. He would set an NCAA tournament record for most free throws made without a miss (35).

“I don’t recall feeling much pressure at all,” Lee said. “It was a feeling of elation to be in that moment and have the opportunity to play for a national championship. We had a good shot, but I think Kentucky just wore us down.”

Lee hit a three with 26 seconds left to force overtime and later made three free throws to keep the Cardinal in it, on the way to 26 points. But Kentucky nailed down a frantic 86-85 victory and went on to win the title.

Moments after the horn sounded, a murmur grew to a crescendo. The 40,000 fans, led by hundreds of members of the coaches’ association at courtside, rose to applaud. The coaches, more than anyone, knew “they’d just witnessed a defining performance, one contest at a level so towering it elevated their sport,” wrote Tom Cushman of the San Diego Union-Tribune.

It was an ovation of appreciation.

In the locker room, “I don’t think there was a dry eye,” said Jamie Zaninovich, the team’s marketing and operations director. “Guys were crushed. It dawned on everybody, we could have won the national championship.”

Montgomery addressed the team, first talking about the game itself, “Then he spent the next half hour talking about how this was the most memorable season he ever had,” Zaninovich said. “He never had a group like that and this would be the last time we’d be together. It was incredibly emotional.”

There always was next year, and the future looked bright. All five starters returned, and Lee made the cover of Sports Illustrated as the magazine touted the Cardinal as the nation’s team to beat. But, there are no guarantees, and Stanford was upset by Gonzaga in the second round of the 1999 NCAA tournament, ending the collegiate careers of Lee, Sauer, Seaton, Weems, and Young.

•••

•••

YOUNG WAS A second-round pick of the Golden State Warriors, but none of the others were drafted in 1999. Lee was so nervous on draft night that he couldn’t bear to wait for a phone call or watch the draft on TV, and went to the movies instead.

He and his father saw, “South Park: The Movie.”

“I don’t remember a single scene,” Lee said. He came home to discover that nobody took him. He was devastated.

Lee moved to Turkey to begin an overseas odyssey that took him to 10 countries in 13 seasons, and met his wife, Maja, along the way, in Croatia. Lee got a brief NBA look when Montgomery coached the Warriors, but didn’t make the team.

“I was just hoping now and then that my agent would call and say, ‘you got a shot,’”Lee said. “But probably four or five years into it, I said, ‘I’m fine.’ I’m making a good living over here. The NBA became a distant memory and a distant dream. That was fine, because after a while, it didn’t really matter much anymore.”

Four players on the 1998 team – Jarron and Jason Collins, Madsen, and Young – played a combined 33 seasons in the NBA. Including overseas, eight played pro ball. And five are coaches: two in the NBA, one in the G-League, and two in high school.

What can 20 years teach? What can the perspective of basketball, played in a young man’s body, offer to those approaching middle age?

“I just wanted to get out there, make a ton of money, and just be rich,” Lee said. “But life is so vast. It’s about the people you meet, and the perspective you can form just by being around different people and different cultures. I was always a genuine person, but now I have a better understanding of the importance of building relationships and embracing humility, and having empathy for all kinds of people.

“Here in the States, we like to get as much as we can. That’s what we’re accustomed to. But living and traveling around the world, I realized bigger is not always necessarily better. It’s about the quality of your life and your perspective that’s really important.”

In 2013, Jason Collins, who played only one game in 1997-98 because of injury but went on to a 13-year NBA career, became the first openly gay athlete to play a major American team sport. He was inspired to reveal his sexuality when hearing that a Stanford roommate attended Boston’s Gay Pride Parade, and Collins had to come to grips with not being honest with himself.

Tshionyi spent two years in the West African nation of Gabon with the Peace Corps before earning a master’s from London School of Economics and Political Science. Tshionyi has combined interests in private investing and social networking into a love of philanthropy and service.

“Stanford was fundamentally a family,” Tshionyi said. “It taught me about resilience and that there are different ways to lead, and not necessarily from the front. I learned that sometimes you have to cede the floor, and that’s something I’ve carried into business.

“Sports are a means to an end. They are a phenomenal way to develop character, and they can have an outsized impact in the world in a positive way.”

Alex Gelbard, a walk-on guard, is a Nashville surgeon specializing in airway reconstruction and remains inspired by Sauer.

“Lots of times we look for symbols of value and people can’t live up to that,” Gelbard said. “Peter is not one of those people. He was a powerful influence. I used to talk to my children about Peter, so they would know how to live with poise and dignity.”

As the owner and operator of a small business, an auto repair shop outside Dallas, Mendez learned through basketball that “nothing comes easy.”

“At Stanford, it wasn’t given to anybody,” he said. “If you want to get ahead, you work hard, put in the time and, at the end of the day, you have to want to be the best that you can be in anything that you do.”

By the way, who was the best shooter on the team? “Hands down, me,” Mendez said.

Not long after the Final Four season, Young’s grandfather, Roy Young, died suddenly. Roy had been Tim’s biggest supporter, attending Tim’s practices almost daily since Tim’s days at Harbor High in Santa Cruz. Tim described him as “a fundamentally stabilizing force,” in his life.

The emotional pain, combined with back problems and media criticism for not being more physical for his stature -- though he was an All-Pac-10 selection -- took a toll. For years, all he wanted to do was play basketball, and now, sometimes he questions whether it was worth it.

But Young, living in Honolulu, always appreciated his teammates and those feelings remain as strong as ever, as he expressed in a recent letter to Tshionyi, his former roommate.

“My daughter, Kaya, had her first rec league basketball game the other day,” Young wrote. “The team is about to warm-up when ‘Eye of the Tiger’ starts blaring out of the speakers. I almost fell over and thought, must this song haunt me and my brood forever?

“I’m only kidding, of course, but it snapped me back into our locker room: Getting taped, preparing for Sauer’s chest bump, Monty’s clinical pregame prep, all the jitters and anticipation, Art’s Westside high-fiving. And then … boom! All of it is over in a flash. And we’re middle-aged and wondering, Where did the time go?”

•••

•••

Where are they now?

Head coach

Mike Montgomery

Retired coach and Pac-12 Network men’s basketball analyst after serving as head coach at Stanford for 18 seasons (1986-2004), with the Golden State Warriors for two, and Cal for six. Inducted into the National Collegiate Basketball Hall of Fame.

Assistant coaches

Trent Johnson

Assistant coach at Louisville after succeeding Montgomery as Stanford’s head coach for four seasons (2004-08) and serving as head coach at Nevada, LSU, and TCU.

Doug Oliver

Retired coach after serving as head men’s coach at Idaho State, as a Stanford assistant under Trent Johnson, and as women’s head coach at UC Irvine.

Eric Reveno

Assistant coach at Georgia Tech after nine seasons as a Stanford assistant and 10 seasons as head coach at University of Portland.

Mark Thompson

Undergraduate assistant coach. Now lives in San Luis Obispo.

Players

David Bennion

Moving from Park City, Utah, to Dallas to become a partner in a new real estate development company and consultancy called Open-Rebees.

Johannes Burge

Assistant professor of psychology at University of Pennsylvania, with a Ph.D. in vision science from Cal-Berkeley.

Jarron Collins

In his third season as an assistant coach for the reigning NBA champion Golden State Warriors after a 10-year NBA playing career. Inducted into Stanford’s Hall of Fame.

Jason Collins

Retired from a 13-season NBA playing career during which he became the first openly gay player in any of the four major U.S. pro sports. Inducted into Stanford’s Hall of Fame.

Alex Gelbard

Assistant professor at the Vanderbilt University Medical Center, in the Department of Otolaryngology, where he specializes in airway reconstruction surgery.

Arthur Lee

Athletic director, health and fitness instructor, and academic advisor at Chicago Bulls College Prep after a 13-year overseas playing career in 10 different countries.

Mark Madsen

Assistant coach with Los Angeles Lakers after a nine-season NBA playing career that included two NBA titles with the same franchise, and a season as a Stanford assistant under Johnny Dawkins.

Mike McDonald

Lives in the Boston area as a Northeast and Eastern Canada regional sales manager for Arthrex, a medical devices company.

Ryan Mendez

Owner and operator of Kwik Kar Marsh, a lube and auto repair business in Carrollton, Texas. Spent two seasons playing overseas.

David Moseley

Assistant athletic director and boys basketball coach at Woodside Priory School in Portola Valley, and founder of A Better Shot, Inc., which produces sport-specific mobile applications.

Peter Sauer

Passed away at age 35 in 2012 after a pickup game in White Plains, N.Y. Played two seasons in Europe and was moving to Pittsburgh after working in investments for Bank of America on Wall Street.

Mark Seaton

Chief financial officer at First American Financial, a title insurance company based in his native Orange County.

Kamba Tshionyi

Director, Client and Philanthropic Services at Align Impact in the Bay Area. Earned a master’s from London School of Economics and Political Science, and served in the Peace Corps in Gabon.

Pete Van Elswyk

Senior Commercial Account Manager at RBC in Toronto after playing overseas for 10 seasons in five countries, mostly in Italy.

Tim Young

A stay-at-home dad in Honolulu, who played one season with the Golden State Warriors and four overseas. He is married to the former Paula McNamee, a volleyball and basketball player at Stanford.

Kris Weems

In first season as assistant coach of the G-League’s Santa Cruz Warriors after serving as athletic director and boys basketball coach at Menlo School and as a college basketball TV analyst.

Athletic Trainer

Jeff Roberts

On the kinesiology faculty and Head Athletic Trainer at Ohlone College in Fremont.

Strength Coach

Scott Swanson

In his 20th year as an Assistant Athletic director/Director of Strength and Conditioning at Army West Point.

Managers

Rafael Ruano

The former head manager is an attorney and Chief Administration Officer at Goyette & Associates, Inc., in Sacramento, and the founder and director of American River Water Polo Club.

Ben Mossawir

The former assistant manager is a Staff Engineer at Google developing imaging electronics for Pixel phones, and has a Stanford Ph.D. in electrical engineering.

David Solow

The former assistant manager is a Vice President in the Investment Management Division of Goldman Sachs in Chicago.

Operations

Jamie Zaninovich

The former Director of Operations and Marketing is now Deputy Commissioner and Chief Operating Officer of the Pac-12 Conference, and former Commissioner of the West Coast Conference.

Paul Rundell

The former volunteer assistant with basketball operations had been the head coach and athletic director at San Francisco State. He passed away in 2005 in Raleigh, N.C.

Michael Wolf

Title was graduate manager, but duties were office oriented. He is now the head coach at Westview High in Portland, Ore., and an advanced regional scout for the Denver Nuggets.

Media Relations

Bob Vazquez

The longtime men’s basketball media relations director is retired and living in the San Diego area. After leaving Stanford in 2007, he spent seven years in the same capacity at Cal State Northridge.

Darcie Bransford Taylor

The former media relations assistant is the West Coast Director of the Jimmy V Foundation and lives in San Francisco.

Office staff

Sandi Peregrina

The former administrative associate is retired and living in Sunnyvale and volunteers at Humane Society Silicon Valley.

Alexandra Dey

The former office assistant graduated from Stanford and lives in Seattle where she operates a skincare salon.

•••